A drover’s flintlock pistol and walking stick that once belonged to the Brae Lochaber drover Alexander MacArthur (1774 – approximately1844) was gifted to the Museum recently. This blog has been written for us by the donor.

Droving cattle was an important part of the Highland economy up to and including the 19th century. The droves consisted of black cattle (bovines) and horses (equines) collectively specified as cattle. The purpose of droving was to meet the needs of the population further south. Highland drovers generally traded at fairs in central and lowland Scotland but were also known to take the livestock further south and on one occasion at least sold as far as the south coast of England, trading as they went.

There were two categories of drovers. There was a class of men who were entrepreneurs who bought the cattle from the farming population in the Highlands and were it seems trusted to pay up on return north if they had not paid before. Another group gave their services for a fee. In between there were others who partly worked for a fee but did some trading. All were referred to as drovers.

In medieval and early post medieval times payment, one imagines, would have been by coin or barter with goods bought in the south. Therefore, a fairly heavily armed group would have been required to protect the cattle from theft on the way south and the revenue on the journey north. This would have been possible up until the Disarming Act of 1746 which made it a capital offence from then on to carry a weapon. Exemptions did apply. Hence drovers were

were permitted to carry a firearm for personal protection and did so into the 19th century. However, the need for such protection diminished. For example, the banking system developed and by the early nineteenth century it was possible for a drover (and others) to deposit their takings in one bank and, with a receipt, withdraw them at a bank in the north.

The pistol shown here belonged to a well-known drover by the name of Alexander MacArthur who lived in Brae Lochaber in the early 19th century. Many of his descendants live in Lochaber to this day. According to what is said of him in the locality he traded on his own behalf. It is not known how able he was in his business, but he did “go bankrupt” as local repute has it. He was on the other hand reputed to be generous to poor people whom he met on his way back north. Whatever it is he died in poverty unable to pay his church dues or satisfy his creditors and is buried in a pauper’s grave. The exact location is unknown. He is also known for building a house replicating the style found in Aberdeenshire which suggests he had business contacts with that part of Scotland. Further research may reveal a yet more interesting and complex character.

This flintlock has been a working pistol. There is no significant ornamentation. It is compact being only six inches long. It is slab butted and therefore narrow so that it can be easily concealed in the folds of a plaid or under a worsted tweed garment for example. Sadly part of the firing mechanism has been lost but it had the “box lock” system introduced into flintlock pistols manufactured in the late 18th and early 19th centuries where the firing mechanism was located within the breech of the pistol effectively reducing the overall width of the pistol in comparison with side slung mechanisms, Box lock pistols were loaded with powder and shot directly into the breech by removing the barrel with a barrel key, which is lost in this instance. There are registration marks on the underside of the breech

There would have been four skills involved in making the pistol. The barrel is likely to have been made from horseshoe nails by a skilled blacksmith. Iron was scarce in Scotland and old horseshoe nails were melted and beaten round a gauge to form a barrel of the correct bore. The breech is of what appears to be cast iron. The stock is of carved wood probably walnut. Making the firing mechanism would have required a similar skill to that of a clockmaker or locksmith of the age.

The makers name Gourlay is shown on the left-hand side of the breech. In 1818 their business is recorded in the Glasgow Directory at Nelson Street, Glasgow and between 1822 and 1836 they were recorded at Argyll Street doing business as C&J Gourlay. It is not known whether MacArthur bought the pistol new from Gourlay’s or acquired it at a later date. It came into my possession when the house at Number One Murlaggan was sold.

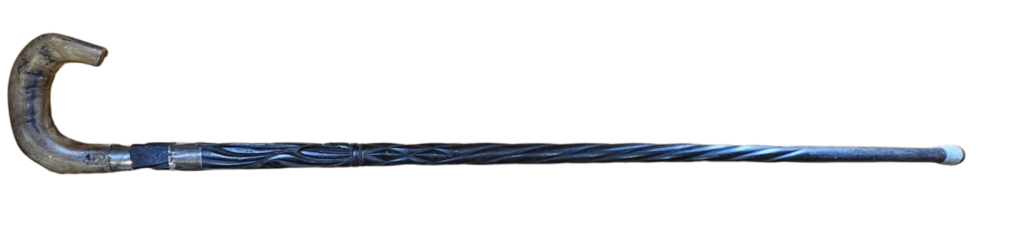

Also donated was a walking stick believed to have belonged to the 19th century Highland drover, Alexander MacArthur. It was passed from Uisdean Campbell to Alistair MacKintosh from whom the donor inherited it from. The shaft is made of ebony and the handle of horn. There is a metal collar covering the joint. A second part is ornamental but damaged at the collar. The stick may have been adapted or added to as parts of it seem modern.

John MacKintosh

Biographical information about the Drover Alexander MacArthur

Source: ancestry.com in Bing

Alexander was born on 20th August 1774 at Breagach, Glenroy, son of John MacArthur, Murlaggan and Sarah Beaton. John died in 1805 age 72 and is buried in Cille Choirill. Sarah was still alive in 1813.

In 1802, Alexander, by now a successful cattle dealer, wrote to the Mackintosh estates from Falkirk asking for a farm in Lochaber offering 120 guineas for Breagach for himself and his brothers stating that he and his forefathers had been brought up there. He was granted this and then in 1804 Bohasky and part of Brunachan were added.

On 18 Feb 1807 he married Ann (Nany) MacDonald (1785–1810), daughter of Angus MacDonald of Inverigan (1730–1815) and Mary Rankin (1741–1821), Glencoe (both buried in Eilean Mundi, Glencoe). Ann was working in Garrygoulach and they were married there.

She was the youngest sister of Archibald MacDonald of the Hudson Bay Company whose story is recorded in the book, Glencoe and the Indians by James Hunter.

Ann possibly died after the birth of her daughter, Mary (1810–1893) but before 1841.

Mary married James MacKintosh, Murlaggan. They had 7 children. One son, Donald, became an Australian MP.

In the 1841 census, Alexander is in Achavaddy with a Margaret MacArthur… new wife or sister or daughter?

In 1823 he was named on the list of removals. Between 1827 and 1844 he rented Achavaddy and Breagach and had the rental of an inn in Fort William but then in 1844 he had large debts and he applied for sequestration.

His main debtor was Drover John Cameron Corriechoillie (John’s mother was a MacArthur so possibly a relation) who took over his affairs. Alexander possibly died shortly after this. So far have not traced his death.