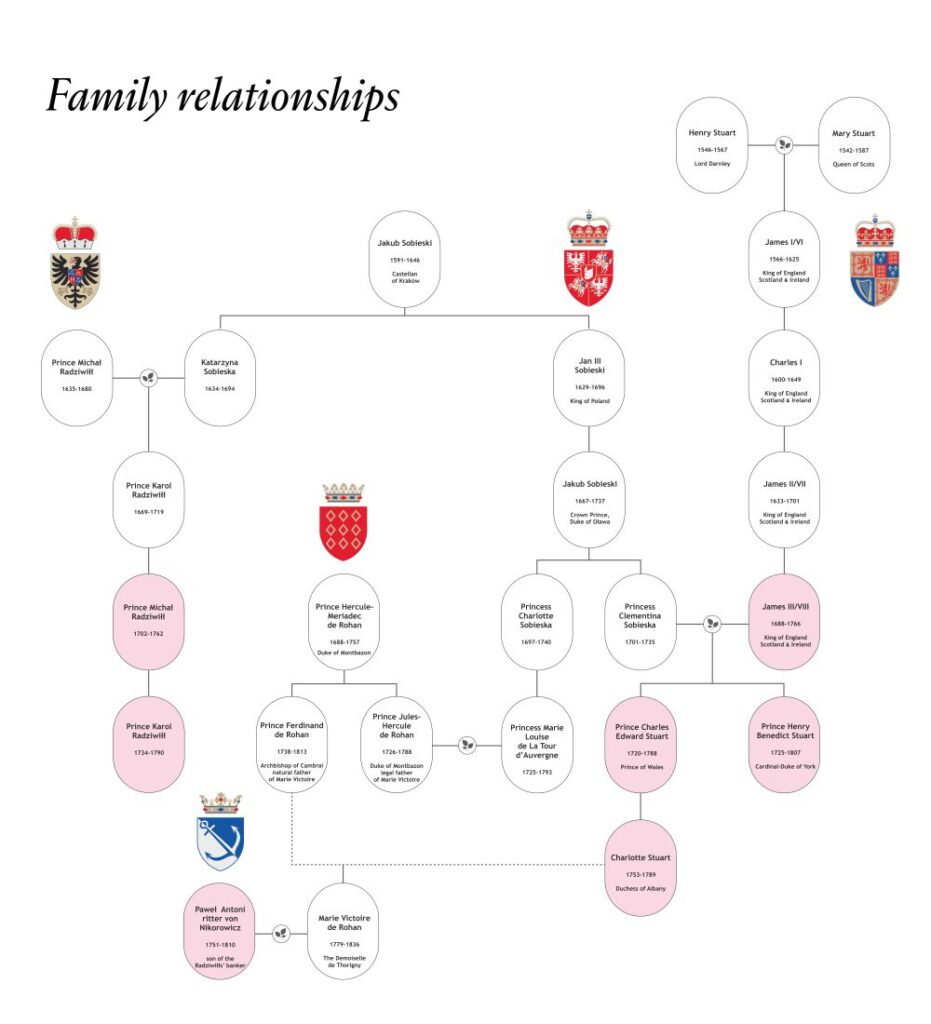

One cannot properly understand the exiled Stuarts in Rome, and the importance of their relationship with Poland, without understanding the role played by one extraordinary individual. That man was the Stuarts’ most trusted confidant. He was also an intimate friend of the Stuarts’ closest Polish cousins, Prince Michał Radziwiłł and his eldest son Prince Karol Radziwiłł.

In 2022 and 2023 the present author published articles in The Stewarts and The Jacobite, and spoke at the annual conference in Falkirk held by the Battle of Muir Trust.[1] This man’s career was described. He was a Venetian called Bishop Giorgio Lascaris. Born in 1706, he died at the end of 1795. Also mentioned were Lascaris’ 115 letters in the Stuart Papers. But in 2024 the present author discovered 1,482 pages of letters in Warsaw’s Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych, or Main Archive of Ancient Acts. They were written by Lascaris to the Stuarts’ cousins Radziwiłł.

[1] This essay relates to the publications by the present author (listed below) which provide greater detail and sources: (a) Bishop Giorgio Lascaris and the Stuarts, The Jacobite, Number 173, Winter 2023-2024, pp47-64. (b) The Roehenstart Family and The Death of Victoire Adélaïde d’Auvergne née Roehenstart, Ibid., Number 175, Summer 2024, pp25-37. (c) Lascaris and the Stuart-Radziwiłł Circle – Rome-Poland 1719-1795, Ibid., https://1745association.org.uk/news-events-and-articles (accessed 31.07.2025). (d) The author’s reflections on Bonnie Prince Charlie – His Life, Family, Legend, https://www.falkirkmuir1746.scot/2023-papers (e) The Roehenstart Family and The Death of Victoire Adélaïde d’Auvergne née Roehenstart, https://www.falkirkmuir1746.scot/ 2024Papers (f) Lascaris and the Stuart-Radziwill Circle, https://www.falkirkmuir1746.scot/ 2025-Papers (all accessed 29.07.2025). (g) Bishop Giorgio Lascaris (1706-1795), Stuart Emissary in Poland, The Stewarts (The Stewart Society), Vol:XXVI, No.3, 2022. (h) A Commentary on The Roehenstart Family … , Ibid., Vol:XXVII, No.1, 2024. Bishop Lascaris & The Stuart-Radziwill Circle – A Sequel, Ibid., Vol:XXVIII, No.2, 2025.

Why is Lascaris so significant? The answer is, that from 1735 until his death sixty years later, no-one knew better than he, both the Stuarts in Rome, and the Radziwiłłs in Poland. In emphasis of this, Lascaris became the exiled King James III/VIII’s chief adviser and contemporaries described him as being ‘continually with the King of England’. When James’ younger son Cardinal Henry Stuart was appointed Archpriest of St Peter’s in 1751, he chose Lascaris as his vicar. In 1753 the Jacobite courtier Henry Fitzmaurice even complained that James ‘hardly listens to my advice any more, since the Prelate Lascaris is now the only one favoured’. And in the 1760s James’ last majordomo, Sir John Constable, wrote that he used to meet Lascaris every evening in the king’s antechamber.

The Stuarts were descendants of King Jan III Sobieski. And the Radziwiłłs were descendants of the king’s sister Katarzyna Sobieska. That is why, after the death in 1737 of Crown Prince Jakub Sobieski, who was King James’ father-in-law, both the Stuarts and the Radziwiłłs were deeply interested in the Sobieski inheritance. And that really mattered to the Stuarts. So too, did the potential of the Radziwiłłs to help their Cause – to regain the thrones of Scotland, England and Ireland. Because, though the exiled Stuarts were royal, the Radziwiłłs were much richer. In fact, they were the richest family in Poland, and one of the wealthiest in all Europe. Friends of Louis XV, and relations of his wife Maria Leszczyńska, the Radziwiłłs also possessed a significant military potential.

The earliest Lascaris letter is from 1736. It was to Prince Michał Radziwiłł. The last is from 1790 and was to Radziwiłł’s eldest son Prince Karol who died the same year, childless.

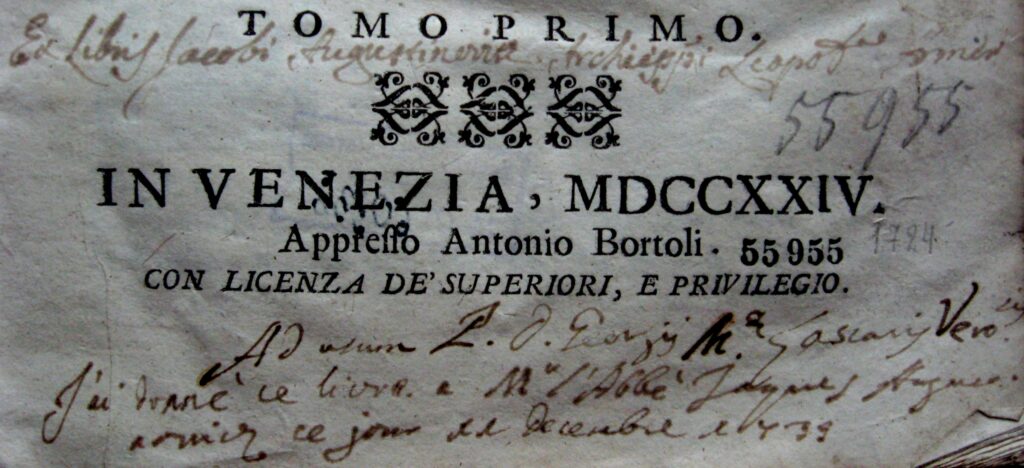

Lascaris was first in Poland in 1735 when he taught at the Theatine College in Lwów, together with the Armenian-Catholic Archbishop Jakub Augustynowicz, of whom more below. Lascaris was then in Rome in 1738, when appointed Prefect of that College, and when the Stuarts made him plenipotentiary for the Sobieski inheritance.

Lascaris was also interested in the Theatine College in Warsaw, to which he had sent his two nephews Teodoro and Giorgio. But he was especially interested in the one in Lwów, of which he had been appointed Prefect. His task there was to strengthen the recent union between the Vatican and the Greek-Catholic as well as the Armenian-Catholic churches. We should recall, that it was the Radziwiłłs’ wealthy bankers Nikorowicz who stood at the head of the Polish-Armenian community in Lwów.

Between 1735 and 1761, Lascaris spent fifteen years in Poland. He had an exceptionally deep knowledge of the country, spoke the language fluently, and knew its leading aristocratic families well. Best of all, he knew the

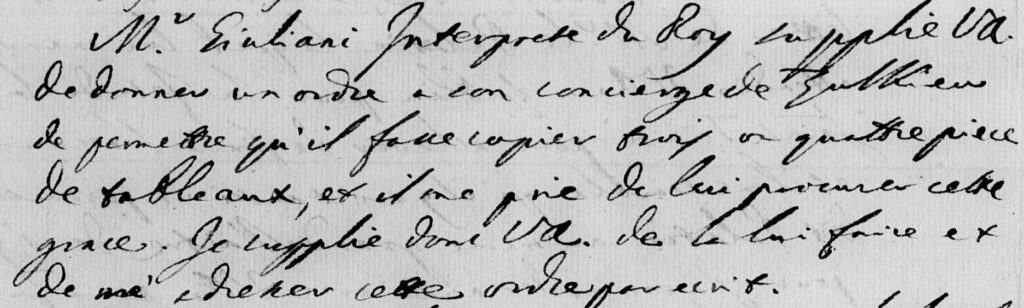

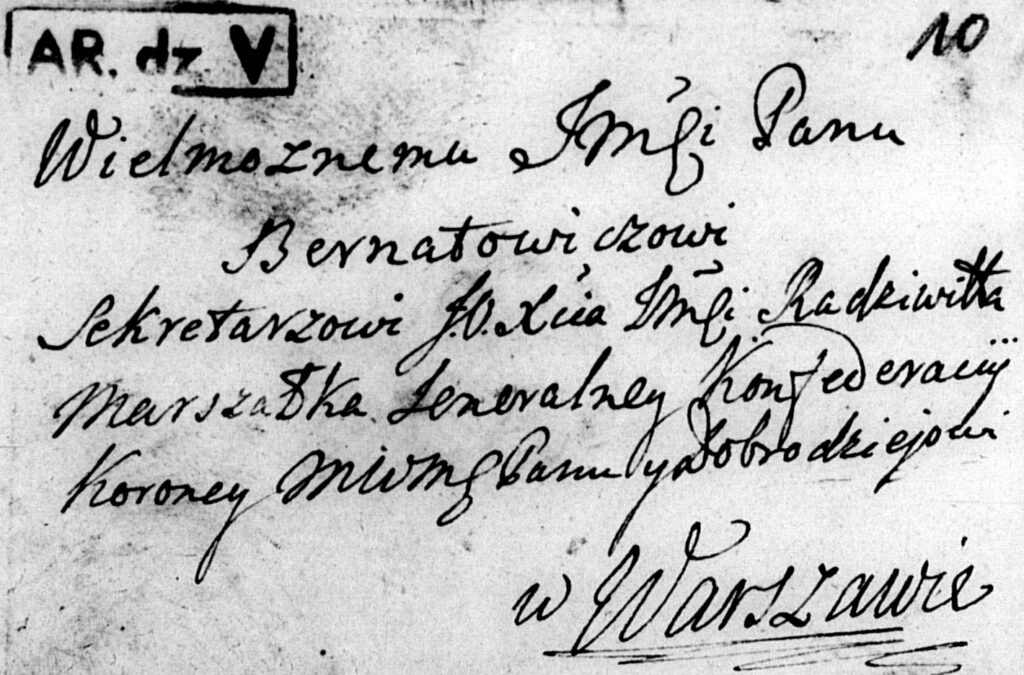

That intimacy meant he also knew their most trusted advisers. They were: the Nikorowicz family (the Radziwiłłs’ bankers in Lwów, who also supplied them with luxury goods from Turkey and Persia), the Nikorowicz cousin Archbishop Augustynowicz, and the Nikorowicz cousins Bernatowicz (who were administrators for the Radziwiłłs). Other advisers were: Pierre Riaucour (who made investments for them), the Fergusson-Teppers (their bankers in Warsaw) and Francesco Giuliani (their Warsaw-based supplier of goods from Turkey).

Lascaris’ letters also show how highly he was valued and trusted by both the Stuarts and the Radziwiłłs, and that via him, for decades, large numbers of letters flowed between the two families. And it is important to realize, that throughout the long years Lascaris spent in Rome at the side of the Stuarts, his influence was very pro-Polish. He was also the Roman Curia’s expert on all matters Polish and in 1764 he was appointed to the Congregation for Polish Affairs. He maintained close relations with the Polish community in Rome and corresponded with his friends and family in Poland until the very end of his life. As recorded in 1796, three paintings at the Cathedral of Łuck by the Polish artist Tadeusz Kuntze had been commissioned and paid for by Lascaris. And when Kuntze painted frescoes at Frascati for Cardinal Henry Stuart in 1775-77, it was at Lascaris’ recommendation.

Let us now call to mind a few relevant facts. On 27 November 1746 King James’ eldest son Prince Charles suggested to him that a bride be found for his brother Prince Henry. He wrote: ‘If Prince Radziwiłł has any daughters of age, I should not think one of them to be an unfit match’. Then, in May 1752, having failed to convince Louis XV to launch another invasion, and been expelled from France, Charles was staying with Radziwiłł on one of his estates. He had just been in Berlin trying to solicit support from Frederick the Great, whilst next-door in Poland, Radziwiłł and his younger brother had a private militia which could field over 6,000 trained and fully armed troops. That was the amount which in 1743 Donald Cameron of Lochiel had said was essential for a rising to succeed. And from 1744, Radziwiłł was the commander-in-chief of one half of the Polish-Lithuanian Army.

A map of Europe shows that Scotland’s east coast was at least as easy to reach from Gdańsk on Poland’s Baltic coast, as it was from Cadiz in Spain to south-west England – the route King James was to have sailed in 1719 – or from Saint-Nazaire in France’s southern Brittany around Ireland’s west coast to Scotland’s Western Isles, as done by Prince Charles in 1745.

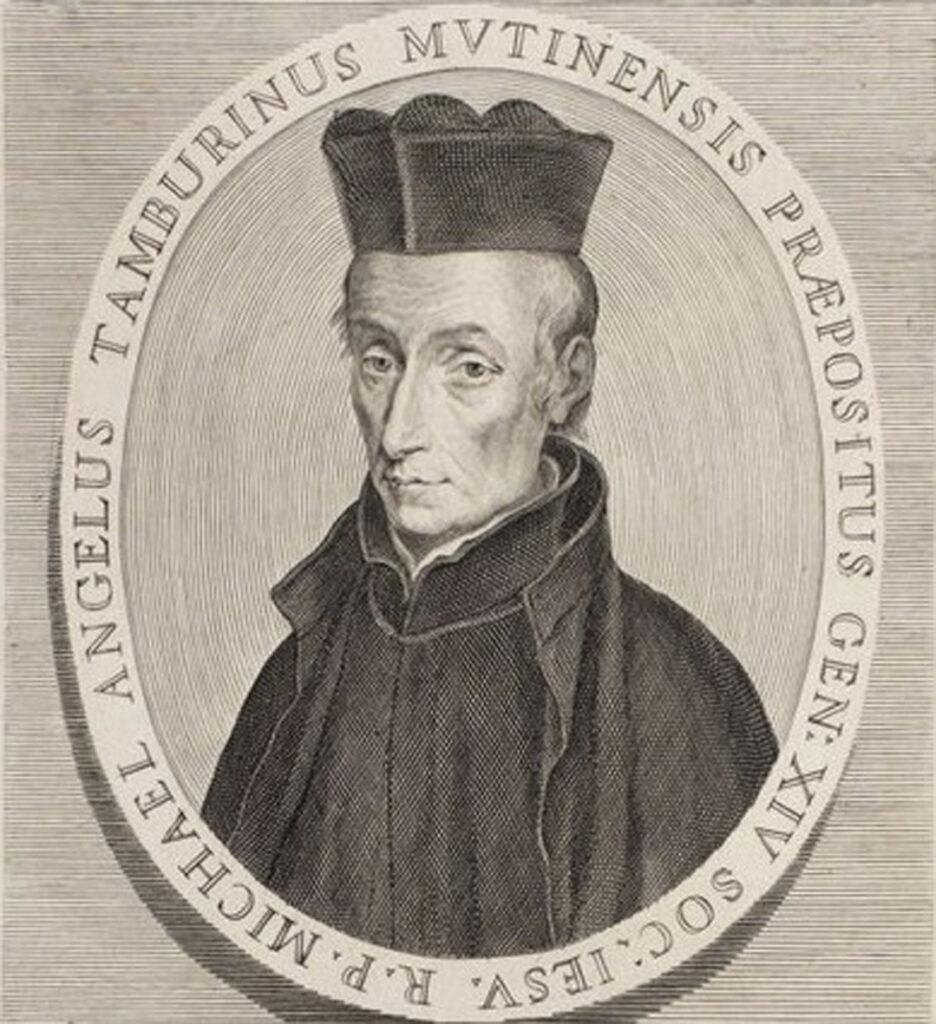

Let us now turn our attention to the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle and its members, and see how interconnected these people were. This circle came into being in 1719 with King James’ arrival in Rome and marriage to Princess Clementina Sobieska. To one of the circle’s first members, attention is drawn by Professor Aleksandra Skrzypietz. In her latest book she describes the moment in late 1725 when Clementina left James for two years: ‘Clementina considered that mothers are treated better in Turkey than the way she was treated in the home of her own husband. She therefore turned to Cardinal Giulio Alberoni, knowing that her husband had greater confidence in him than in many others. She took the decision to leave and live in a convent, and that she would be represented in talks with her husband by Alberoni or by the General of the Jesuits, Michelangelo Tamburini, whom he also trusted.’

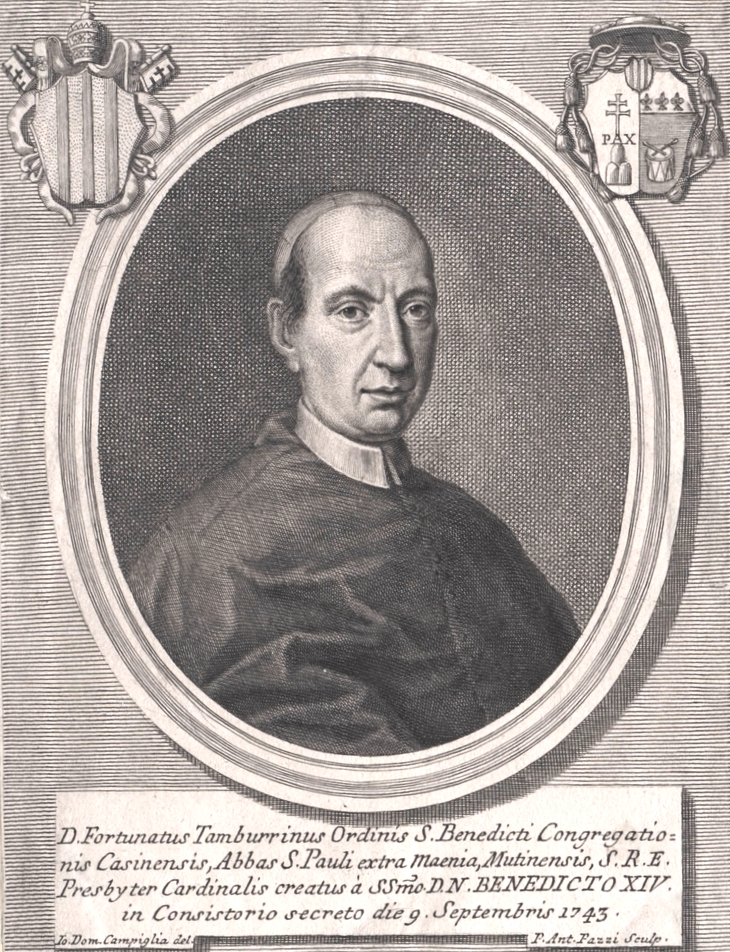

Tamburini was indeed trusted – and not only by King James. He had been the personal theologian of Rinaldo d’Este, Duke of Modena, the younger brother of Alfonso IV, who was King James’ grandfather. Furthermore, Tamburini had a nephew. He taught him theology. He was Fortunato, the son of Simone Tamburini who was also close to the Duke of Modena, being his councillor. Put simply, the Stuarts and their relations the Dukes of Modena, knew the Tamburini family very well indeed.

Tamburini’s nephew Fortunato became a cardinal in 1743 and was then appointed Prefect of the Dicastery for the Eastern Churches, and assigned to the congregation of Propaganda Fide. In 1752 he became a Protector of the Greek College in Rome. By comparison: Lascaris had been appointed by the congregation of Propaganda Fide as Prefect of the Theatine College in Lwów, responsible for strengthening Rome’s union with the Eastern Churches, whose Greek-Catholic and Armenian-Catholic cathedrals were both in Lwów. Therefore, Lascaris and Fortunato Tamburini were close colleagues.

Lascaris’ letter to Radziwiłł, sent from Rome in 1750, reveals how both helped Poles study in Italy. Lascaris tells Radziwiłł: ‘Ciedzielewski has greatly profited, and all that is required is for him to spend two or three months under the famous Tartini in Padua, when he will stay with my friends and relations in Lombardy’.

To summarize: Lascaris and Tamburini were close colleagues, both were core members of the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle, and Lascaris not only encouraged Poles to go and study in Italy, but also Italians, like his nephews Teodoro and Giorgio, to go and study in Poland. It is no surprise, therefore, to see a Brygitta Tamburini in Lwów, who died there in 1767 aged three. Nor a Grzegorz Augustynowicz, who was baptized in Lwów in 1777, whose godmother was Jadwiga Tamburini. Significantly, the godfather of that child was Grzegorz Nikorowicz, who was not only his grandfather, but also the Radziwiłłs’ banker.

Equally significant, is the fact that the priest who baptised Jadwiga Tamburini’s godson was Grzegorz’s son, Abbé Marek Nikorowicz, who had only just returned to Lwów from Rome where he’d become a doctor of theology in 1775.

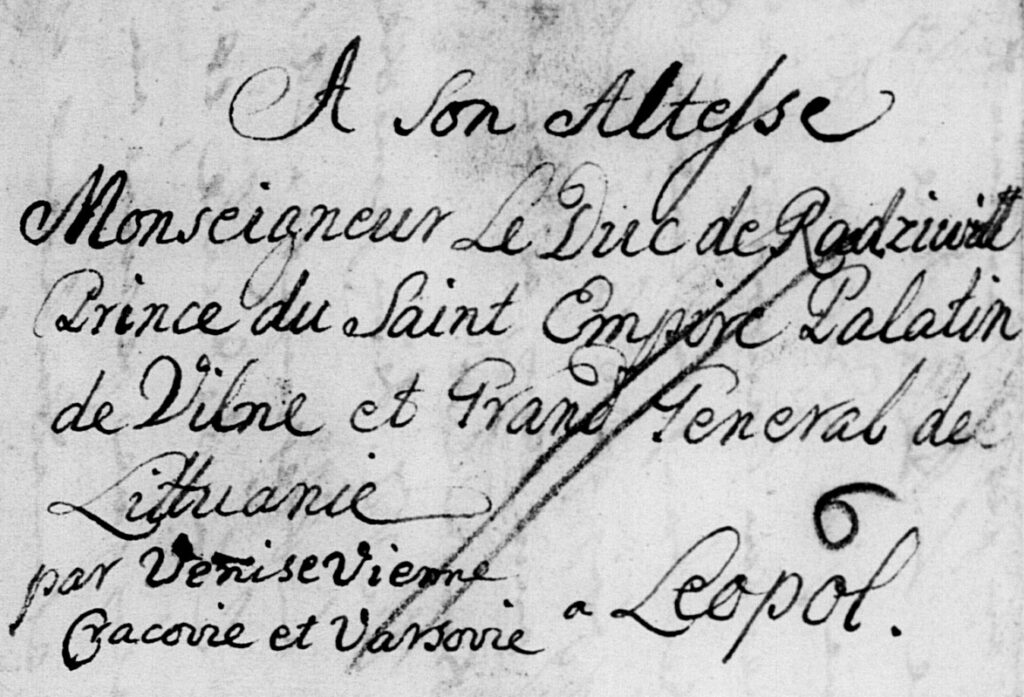

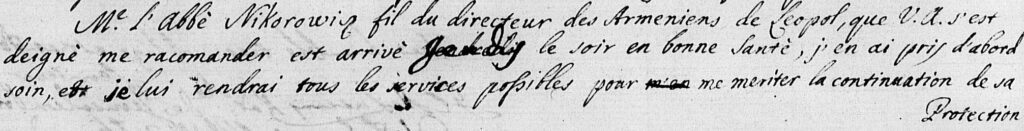

The present author’s articles of 2022-2023 presumed that Abbé Marek’s studies in Rome had been arranged for him by Lascaris and Radziwiłł. Because his father Grzegorz’s 1781 letter to Radziwiłł referred to ‘half a century of my life during which I have had the honour of being graced by your Serene Highness’. And because Abbé Marek himself wrote to Radziwiłł in 1775 of ‘the grace and protection Your Highness has always extended to my whole family’. Now, thanks to Lascaris’ newly-discovered letters, it transpires that this earlier presumption was correct. Because Lascaris’ 1774 letter from Rome to Radziwiłł states that: ‘The Abbé Nikorowicz, son of the director of the Armenians of Lwów, whom Your Highness deigned to recommend to me, arrived here on Thursday evening in good health; I took care of everything at once, and will render him all possible services so as to continue to merit your ducal protection’.

Now we begin to appreciate the consequences of these Stuart-Radziwiłł connections. Because Abbé Marek’s younger brother was the same Paweł Nikorowicz who in 1803 married Bonnie Prince Charlie’s granddaughter, namely Charlotte Stuart’s eldest child Marie Victoire de Rohan. She was Paweł’s fourth wife. Another letter reveals that around the time of Paweł’s first marriage, he was living abroad. That letter was from his father Grzegorz to the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II. Evidently, when Lascaris and Radziwiłł arranged for Abbé Marek Nikorowicz to go and study in Italy, his brother Paweł went too. Because, soon after, he married his first wife. She was none other than Caterina Tamburini, from the same family as the Stuarts’ trusted Jesuit Michelangelo, and Lascaris’ colleague Cardinal Francesco.

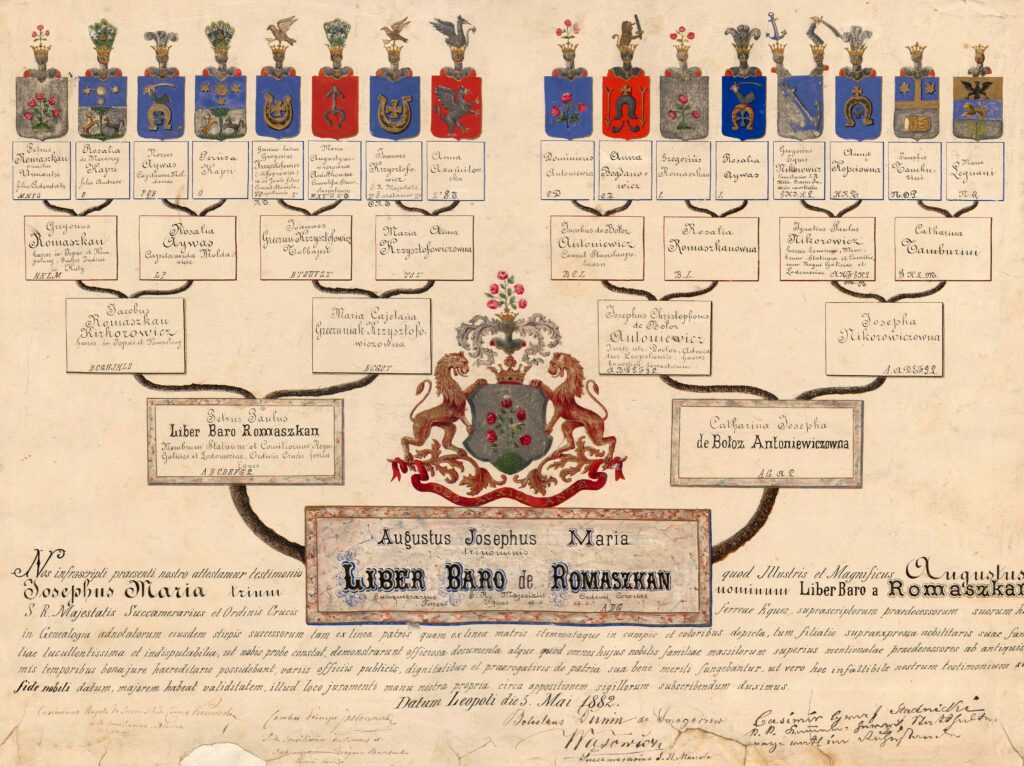

This Nikorowicz-Tamburini marriage is included on the 1882 official proof of nobility for Paweł and Caterina’s great-grandson, Baron August Romaszkan. It is in Kraków’s Jagiellonian Library. And this marriage reveals something of fundamental significance. It proves, that long before Paweł Nikorowicz married Charlotte Stuart’s daughter in 1803, he had already been connected to the Stuarts for thirty years, through his first wife’s family of Tamburini, whom he met through the Stuarts’ confidant Lascaris and their cousin Radziwiłł.

Grzegorz Nikorowicz’s letter to Joseph II describes his other two sons. The eldest was Jan. He married Zofia Augustynowicz, from the same family as Jadwiga Tamburini’s godson and the Armenian-Catholic Archbishop of Lwów with whom Lascaris had taught and whom he described to Radziwiłł in 1743 as ‘such a good friend of Your Highness’. Evidence of Lascaris’ own friendship with Augustynowicz is on the frontispiece of a book belonging to the Stefanyk Library in Lwów. Lascaris’ inscription reads: ‘J’ai donné ce livre a Monsignor l’Abbé Jacques Augustynowicz ce jour, 11 décembre 1739’.

From 1763-72 Grzegorz Nikorowicz’s son Jan was attached to the Polish Embassy in Constantinople where he was one of the first four pupils at the Polish Oriental School. Two others were Pietro and Enrico, the sons of Francesco Giuliani, an Italian polyglot who imported luxury goods from Turkey for the Radziwiłłs. Lascaris’ letters mention him frequently.

This Giulani connection lasted a long time. And again, we see the effects of the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle. Because in 1835 Charlotte Stuart’s son Charles, received money from the sale in Vienna of a ‘grand and magnificent palace’. The sellers were the Giulianis. And here one should recall that Charlotte Stuart’s son Charles, after his sister Marie Victoire’s marriage in 1803, became the Nikorowicz’s brother-in-law, they being old friends of the Giulianis, both families being members of the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle.

Grzegorz Nikorowicz’s youngest son was Józef. He was a distinguished lawyer in Vienna and politician in Kraków. Lascaris’ letters prove that in Rome, King James, Cardinal Henry Stuart, and Lascaris did all they could to facilitate Karol Radziwiłł’s divorce in 1760. Likewise, in Vienna, Józef Nikorowicz did all he could in 1786 to facilitate the divorce of Radziwiłł’s younger brother Hieronim. Of note too, is the fact that Grzegorz Nikorowicz’s mother was from Lwów’s oldest Polish-Armenian family, Bernatowicz. And Grzegorz’s cousin Jakub Bernatowicz was another key member of the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle. In 1764, he was Karol Radziwiłł’s secretary.

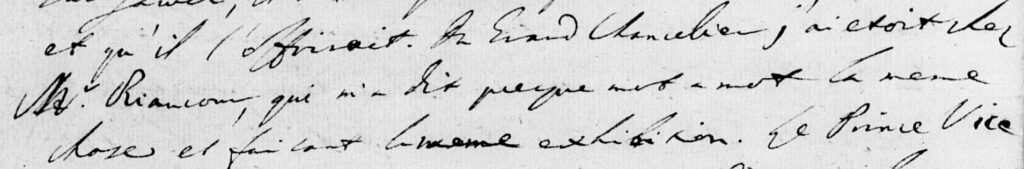

In his letters Lascaris regularly mentions two French-born brothers, Pierre and Louis Riaucour. Pierre arranged and managed investments for the Radziwiłłs, whereas Louis was a bishop whom the Radziwiłłs appointed priest to their Biała estate, where Lascaris was a frequent guest. Pierre Riaucour owned the Pod Czterema Wiatrami palace (Under the Four Winds Palace) on Warsaw’s Długa Street. In 1765 he sold it to the Radziwiłłs’ Warsaw bankers, Fergusson-Tepper. Yet again we see the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle in action. Because The Oban Times published two eye-catching letters in Scotland in 1939. Written by a certain Gordon and Morvern, they state that two of Charlotte Stuart’s children, Charles and Marie Victoire, were ‘secretly adopted by a family in Warsaw named Fergusson-Tepper’. Gordon and Morvern clearly had no idea who the Fergusson-Teppers were, nor of their importance within the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle. Their mention of such a significant name stamps their statement with the hallmark of authenticity, suggesting that their ancestors heard it from Charlotte Stuart’s son Charles before his death when visiting friends in Perthshire in 1854.

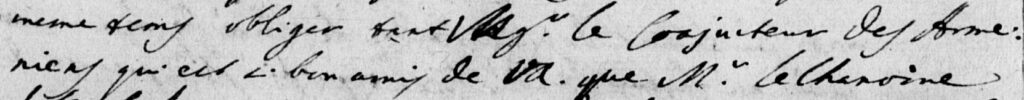

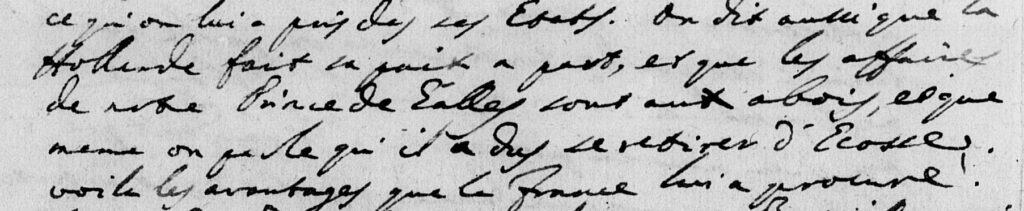

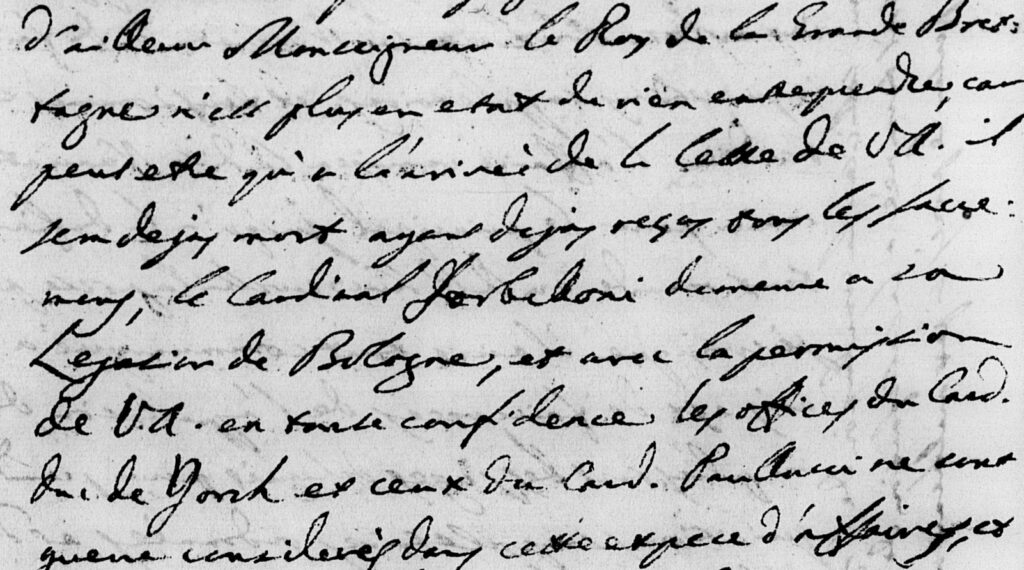

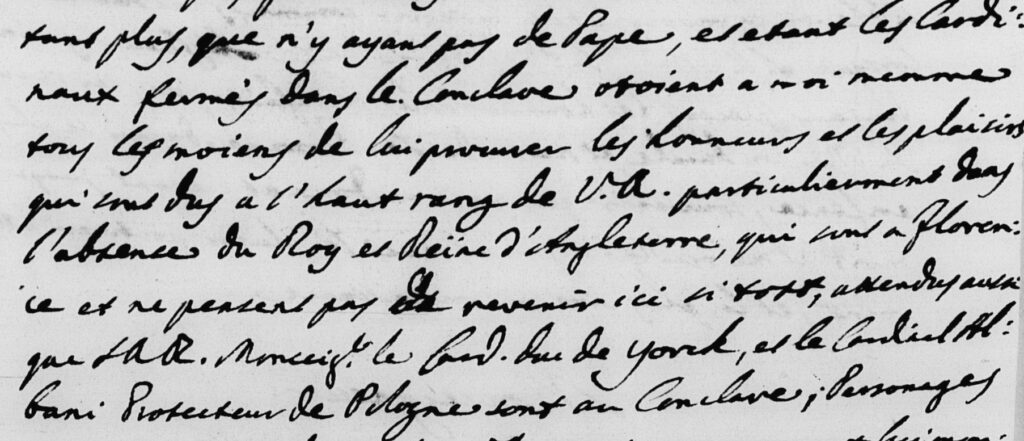

We have seen how inter-connected were the members of the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle. But what do Lascaris’ letters tell us about King James and his two sons Charles Edward, Prince of Wales, and Henry Benedict who, on 3 July 1747, became Cardinal-Duke of York? On 24 January 1746 Lascaris told Radziwiłł that: ‘The affairs of the Prince of Wales are not going well’. Then on 25 May: ‘The affairs of our Prince of Wales are desperate, and it is said that he is forced to retire from Scotland. Such are the advantages France has given him!’

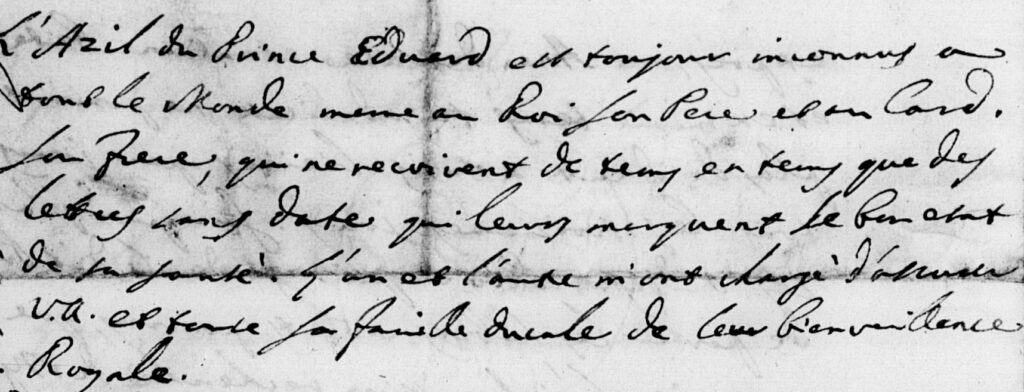

By 31 December 1749 Lascaris wrote to Radziwiłł: ‘His Majesty is well, and so is the Cardinal York. As for the Prince of Wales, one speaks nothing of him and it is forbidden to mention him to the King, nor do we know where he is, yet some claim he is in Scotland.’ On 26 April 1750 he said: ‘As regards the Prince of Wales there is nothing new, only a brief letter which arrived fifteen days ago, giving neither date nor place, just telling His Majesty that he is well.’ On the 22 August Lascaris added: ‘The refuge of the Prince Edward [the name by which the French called Charles] is constantly unknown to everyone, even the King his father and the Cardinal his brother, who from time to time receive undated letters which mention only that he is in good health. Both of them instruct me to assure Your Highness and all the ducal family of their Royal goodwill.’

By 27 October 1750 Lascaris was complaining to Radziwiłł: ‘How can one succeed in this matter so long as the older Prince is so well hidden from sight and the place of his residence unknown to the King his father […] it seems with evidence, that the signature of the Prince of Wales will presently be even more necessary, being that of the person principally interested in this matter.’

In 1752 Lascaris negotiated Cardinal Henry’s return to Rome from Bologna after his bitter argument with King James, caused by his ambiguous relationship with the attractive young priest Giovanni Lercari. Such was his tact that Henry placed his complete trust in Lascaris. On 8 July Lascaris told Radziwiłł: ‘He [Henry] would like me to come and reside in the Royal Palace, dine at his table and drive with him in his carriage, but that would be too much too soon and give rise to jealousy.’ By 14 October 1752 he wrote: ‘This Prince [King James] continues to be afflicted by the absence of his two sons, the first of whom continues to remain so hidden that there is no news of him, whilst the second is still in Bologna, although he is thinking of returning to Rome.’

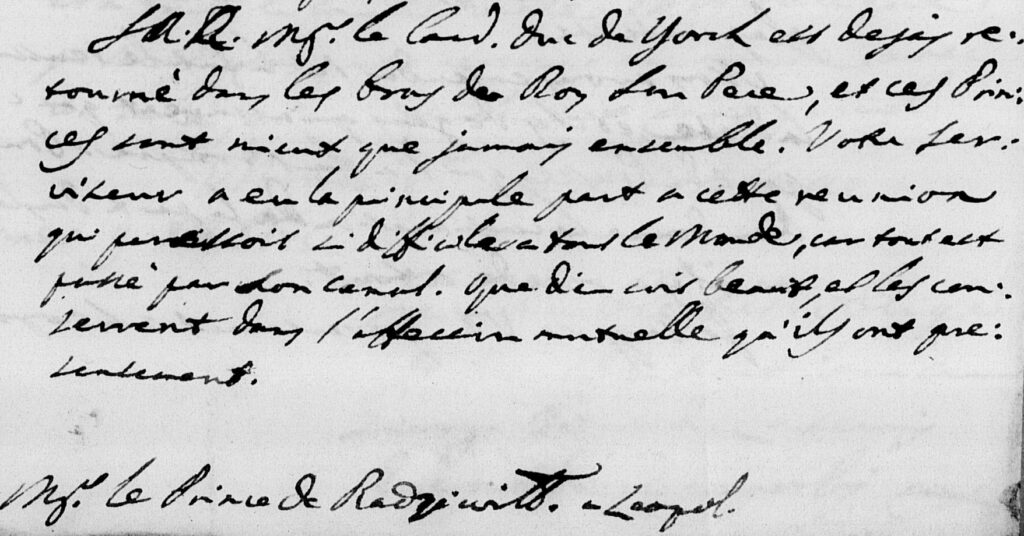

On 9 December 1752 Lascaris triumphantly informed Radziwiłł: ‘His Royal Highness the Cardinal Duke of York has returned to the arms of the King his father, and these Princes now get on better than ever before. And it was your humble servant who played the principal part in this reunion which seemed so difficult to everyone.’

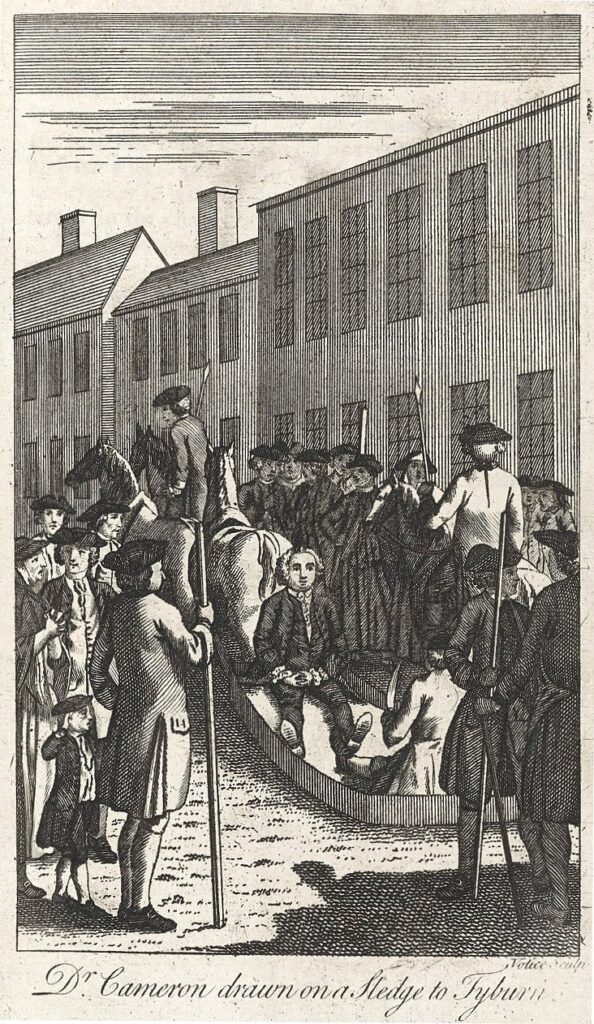

At the time of the failed Jacobite plot led by Alexander Murray of Elibank, about one month after the execution in London of the faithful Stuart supporter Dr Archibald Cameron, Lochiel’s younger brother, Lascaris wrote to Radziwiłł from Rome on 14 July 1753: ‘There is talk here that King George’s death has occurred in England, and because his grandson is a minor, one may foresee dissention between the Parliament and Regency which may open a path for the supporters of King James to replace him on the Throne. If this accident is true, then it would appear that we do, after all, have news of the Prince of Wales.’ On 8 September he added: ‘Of the Prince of Wales, one still knows nothing of his whereabouts, but it is nonetheless believed that the people recently arrested in Scotland were his emissaries […] which proves that the Prince rests not, but is working towards finding a way to the throne of his father.’

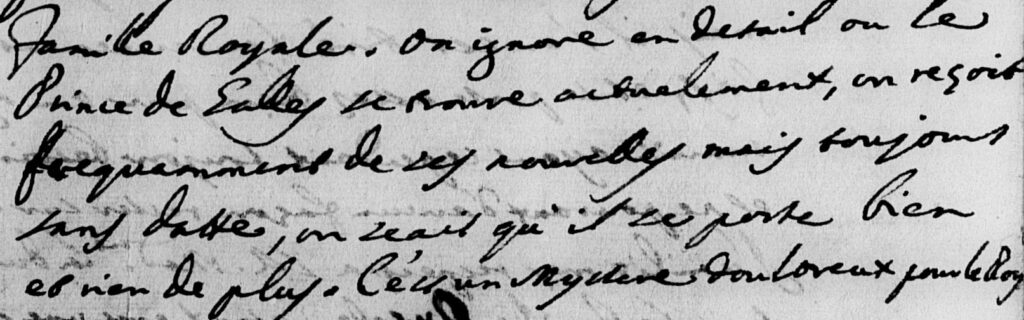

During the period 1757-59 the French again wanted to use Prince Charles Edward, inviting him to lead their attack on Minorca, and later, a planned invasion of Ireland. On 8 May 1757 Lascaris told Radziwiłł that: ‘It is said the Prince of Wales is presently in negotiations with the Marshal de Belle-Isle, to make a descent upon England or Scotland.’ But by 3 September he wrote in frustration: ‘I believe an internal revolution of those countries is the only way to replace His Majesty on the Throne, in the person of the Prince of Wales, who, thank God, is well and sends news from time to time to the King his father, however without giving the place where he is staying.’ On 12 October Lascaris added: ‘One does not know in detail where the Prince of Wales is at present, receiving his news frequently, but always without a date, saying that he is in good health, but nothing more. It is a sad mystery for the King.’

Then, on the 16 June 1759, Lascaris informed Radziwiłł that: ‘The King has not been too well for the past year, having fallen into a sort of languor, but His Royal Highness [Henry] is a marvel.’ Then, on 20 May 1760: ‘The King of Great Britain is no longer in a state to undertake anything and seems almost dead, having already received all the Sacraments […] and with Your Highness’ permission, in all confidence, the offices of the Cardinal Duke of York and Cardinal Paolucci are hardly adequate for this sort of a matter.’

King James rallied but was ill again by 1764. He died on the first day of 1766. Prince Charles then returned to Rome. In 1772 he married Princess Louise zu Stolberg-Gedern. Charles’ daughter Charlotte came from Paris to protest, which infuriated both her father and her uncle Henry. Once more, Lascaris’s tactful hand smoothed things over between the Stuarts.

One of Lascaris’ last Stuart-related letters is from 15 January 1775, during the conclave from October 1774 until February the next year. Henry was then very busy as vice-dean of the College of Cardinals, so Lascaris urged Radziwiłł to delay coming to Rome, because, ‘not having a Pope, and the Cardinals being locked in the Conclave, it would remain to me alone to show all the honours and pleasures due to Your Highness’ rank, particularly given the absence of the King and Queen of England who are in Florence and do not think of returning here.’

In fact, Prince Charles did return to Rome, at the end of 1785. By then he’d parted from his wife Louise in 1780, made his daughter Charlotte his heir as Duchess of Albany in 1783, then asked her in 1784 to come from Paris and live with him in Florence. That she did. But during the five previous years, believing she had no hope of recognition by her father, Charlotte had given birth in France to her secret children by Prince Ferdinand de Rohan, Archbishop of Cambrai.

Charles died in 1788, Charlotte in 1789, and their cousin Karol Radziwiłł in 1790. In 1795 Ferdinand de Rohan fled the French Revolution and arrived in Rome. There he met Lascaris, as he surely did, both being high-ranking prelates, both having been so close to the Stuarts. By then, Charlotte’s children were safely out of France. But Ferdinand de Rohan was cut off from all his income and urgently needed help to secure their future. He therefore had the strongest of reasons to seek assistance for Charlotte Stuart’s children. And Lascaris had the both the motive and the means to help.

It was natural for Lascaris to think in terms of Poland. The country was a safe haven for French refugees, including Louis XVIII and the exiled royal family. And the Polish-speaking Lascaris had a strong affection for the country’s people and culture. He had even brought his own nephew Teodoro to Poland who, under Radziwiłł patronage, had become a major-general in the Polish Army, married the Polish aristocrat Anna Zabiełło with whom he had four Polish children: Wojciech, Zofia, Jerzy and Teodor, their surname polonised as Laskarys.

As for the Stuart-Radziwiłł circle, apart from Lascaris in Rome, its last surviving core members included the Nikorowicz family in Lwów and the Fergusson-Teppers in Warsaw, colleagues of one another as co-bankers to the Radziwiłłs. In seeking help for Charlotte Stuart’s children, Ferdinand could not admit he was their father. But six years after her death, he could reveal that Charlotte was their mother. Lascaris’ letters never mention the name Rohan, yet would have done had he known the family. What mattered to him, was that these were children of Charlotte Stuart, whom he had known for years, and to whose family, as well as to the Radziwiłłs, he had been unceasingly loyal for six whole decades. It was a loyalty he shared with the Nikorowicz and Fergusson-Tepper families. And that provided the motive to help Charlotte Stuart’s children in the late 1790s when an introduction by Lascaris to the wealthy Nikorowicz and Fergusson-Tepper families was exactly what Ferdinand needed.

So it was, that in 1803, Charlotte Stuart’s first child, Marie Victoire, became the fourth wife of Paweł Nikorowicz, the son of the Radziwiłłs’ banker and the widower of Caterina Tamburini, from the family of the Stuarts’ trusted Michelangelo and Lascaris’ colleague Francesco. Before that date, Ferdinand had been in Warsaw, in 1799, where Marie Victoire and her brother Charles were said to have been ‘secretly adopted by a family named Fergusson-Tepper’. And in 1807, that brother Charles was granted an unusually privileged position within the family of General Prince Alexander of Württemberg, based in the old Polish city of Witebsk. And the Württembergs, together with the Radziwiłłs, had been key clients of the Fergusson-Teppers.

To conclude: Lascaris’ letters prove the existence of an exceptionally inter-woven group of people surrounding, and including, the Stuarts in Rome and the Radziwiłłs in Poland. And he was the go-between. It was he who helped Italians go to Poland, like the Tamburinis and his nephews Teodoro and Giorgio. It was he who arranged for Poles to go to Italy, like Abbé Marek Nikorowicz whose brother Paweł’s first marriage was to a Tamburini. It was he who advised the Stuarts and the Radziwiłłs on their most private affairs, and kept both families in touch with one other. And the evidence points to the fact that it was he who put Ferdinand de Rohan in touch with the Radziwiłłs’ bankers Nikorowicz and Fergusson-Tepper, from whom the former provided a rich husband for Charlotte Stuart’s daughter, and the latter a promising future for Charlotte Stuart’s son.

Moreover, Lascaris’ letters provide a fascinating and broad context to the history of the last Stuarts. They give firm dates for events, and reveal the atmosphere surrounding the exiled royal family. And they show how important their cousins Radziwiłł were to the Stuarts. Revealing, is Prince Charles’ suggestion to his father of a Radziwiłł bride for his brother. Because, Charles did not discover the Radziwiłłs when in Scotland, during his legendary attempt to regain the Stuarts’ thrones. He already fully appreciated their great political, military and financial potential, when still young, in Rome, long before he launched his fateful rising of 1745.

Note on the author:

Peter Pininski is a graduate of Sotheby’s Institute of Art and has lectured internationally on the last Stuarts for institutions such as the National Trust for Scotland. He has been a guest speaker at the Edinburgh International Book Festival and is the president The Lanckoronski Foundation, Liechtenstein, a member of the advisory board of the National Art Gallery of the Ukraine in Lwów, an advisor to the director of the Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków, and to the Ossolineum National Institute in Wrocław, Poland. He is a member of the Biography Committee of the Polish Academy of Learning (Polska Akademia Umiejętności), co-curated with Professor Edward Corp the 2022 exhibition on the Stuarts at the West Highland Museum in Scotland, was consultant to the exhibition on the Stuarts and Sobieskis at the Palace-Museum of Wilanów in Warsaw in 2025, and is the author of various publications on the Stuarts, his most recent book being Bonnie Prince Charlie – His Life, Family, Legend, published by National Museums Scotland in 2022.

Illustrations:

All letters illustrated belong to the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in Warsaw, (Main Archive of Ancient Acts), Radziwiłł Archive, see Lascaris/Laskarys: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/seria?p_p_id=Seria&p_p_lifecycle=0&_Seria_id_serii=736717&_Seria_nameofjsp=jednostki&_Seria_sygnatura=1%2F354%2F0%2F5&_Seria_tytul=Lascaris&_Seria_data_od=1700&_Seria_data_do=1800

Almost all are in French and accessible on-line, being in chronological order (accessed 18.09.24).

Baron Romaszkan’s 1882 proof of nobility is in the Jagiellonian Library of the University of Kraków

Other illustrations are the property of the author, except the following which are in the public domain and whose ownership or custodianship the author would like to acknowledge:

- Prince Michał Radziwiłł, by Augustyn Mirys: National Arts Museum of Belarus

- Prince Karol Radziwiłł, after Konstanty Aleksandrowicz: National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

- Archbishop Jakub Augustynowicz: The Armenian-Catholic Parish, Armenopolis, Romania

- Prince Charles Edward Stuart, by Étienne Parrocel: Casa de Alba Foundation, Madrid, Spain

- Prince Henry Benedict Stuart, by Étienne Parrocel: National Museum, Kielce, Poland

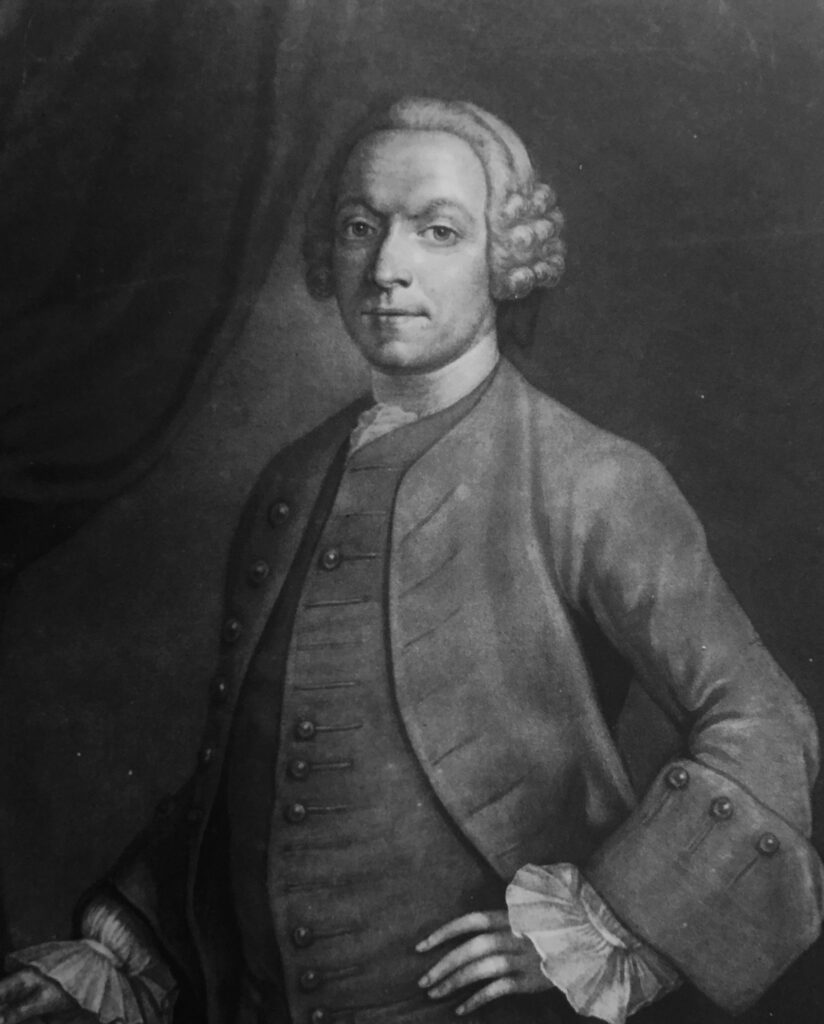

- Donald Cameron, 19th of Lochiel: The West Highland Museum, Fort William

- King James III/VIII, by Anton Raphael Mengs: National Portrait Gallery, London

- Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal-Duke of York, by Anton Mengs: Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France

- Charles Edward Stuart, Prince of Wales, by Katherine Read, Mells Manor, Somerset (an oil on canvas interpretation painted in Rome in 1750-53 derived from, but not identical with, Maurice Quentin de La Tour’s lost original pastel of 1747, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1748. Katherine Read had seen the prince in Scotland in 1745/46, left for France in 1746 and studied with La Tour in Paris until her departure for Rome in 1750. But whereas La Tour’s original shows the prince wearing a powdered periwig, Read paints him with his natural hair in its true reddish-fair colour. She also removes the English Order of the Garter with its star displayed in La Tour’s original, leaving only the Scottish Order of the Thistle. This, when worn on its own, without the Garter, she correctly shows with a blue, not a green, sash. The manifest Scottishness of this important, under-appreciated and hitherto wrongly attributed portrait, strongly suggests it was painted by the Scottish artist for King James III/VIII’s private secretary James Edgar (1688-1762), who was also a Scot. Intended by the then self-confidant Read as an advertisement of her skill to the Stuart Court in Rome, but which bore no fruit, it is one of a matching set of three. The other two are far less impressive copies of the most recent portraits available in Rome of King James and Cardinal Henry, painted respectively by Domenico Duprà (oil on canvas, 1740) and La Tour (pastel on paper, 1746). They would have hung in Edgar’s apartment in the Palazzo del Re until his death on 10/11 October 1762 and then remained in the Stuarts’ possession, though they do not appear in any of the Stuart inventories. Years later, when Cardinal Henry was forced to flee Rome in 1798 because of Napoleon’s invasion and found himself in difficult financial circumstances, a British pension of state was arranged for him, thanks in part to Sir John Cox Hippisley (1746-1825) who had semi-officially represented the British government at the court of Pope Pius VI from 1792–95. In thanks, Henry gave the set of three portraits by Katherine Read to Sir John. His wife was Elizabeth née Horner of Mells Manor and the paintings remain in that house, acquired by their present owners by marriage. For further detail see: E.Corp, A Recently Identified Scottish Portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie by Katherine Read, The Burlington Magazine, October 2025).