In 2025 the museum were gifted Alexander Finlayson Beaton’s wartime medals by his daughter Maggie Hardy (nee Beaton) and granddaughter Tracy Anderson. This fascinating account of Grandpa Beaton’s wartime experiences was written by his granddaughter and has also been gifted to the museum. It is published here by kind permission of Tracy Anderson.

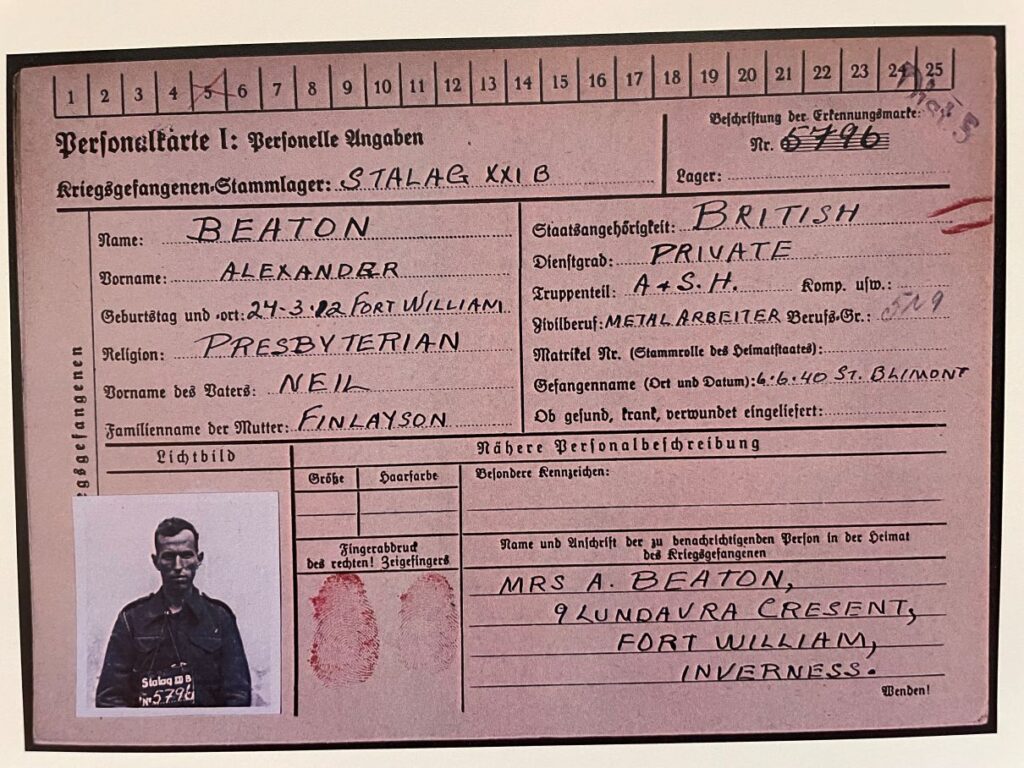

Alexander Finlayson Beaton, known fondly as Grandpa Beaton, was born in Fort William on March 22, 1912 (though his POW record mistakenly notes March 27). In his twenties, he worked at the British Aluminium Company Ltd.’s Aluminium Smelter in Fort William, and during a night out at the Corpach Hotel, he met Mary Anne Budge, who would later become his wife. She hailed from Kilmuir on the Isle of Skye but had moved away as a teenager to work in service for Lady Mary Louise Douglas Hamilton, the Duchess of Montrose, at Brodick Castle on the Isle of Arran. Later, she left Arran to work in Fort William, where she took a job at the Corpach Hotel. Several months later, in 1938, Granny and Grandpa married at the Free Church in Kilmuir, Isle of Skye. He was 26 years old, and she was 24. Their first son, Neil MacAskill Beaton, was born in Fort William on Christmas Eve that same year.

Grandpa was a territorial army volunteer with the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 8th Battalion, and in the late spring of 1939, he left Fort William with his regiment to begin training, in preparation for the nearing outbreak of WW2 in Europe. He completed some of his preparatory training in Aldershot, ahead of the Argyll’s being sent to France in early 1940 and, in June of that year, he was involved in intense fighting in northern France under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Grant. The 8th Battalion faced relentless mortar, machine gun, and artillery fire during this ordeal, and he later spoke of the severe hunger he endured due to the extremely limited rations.

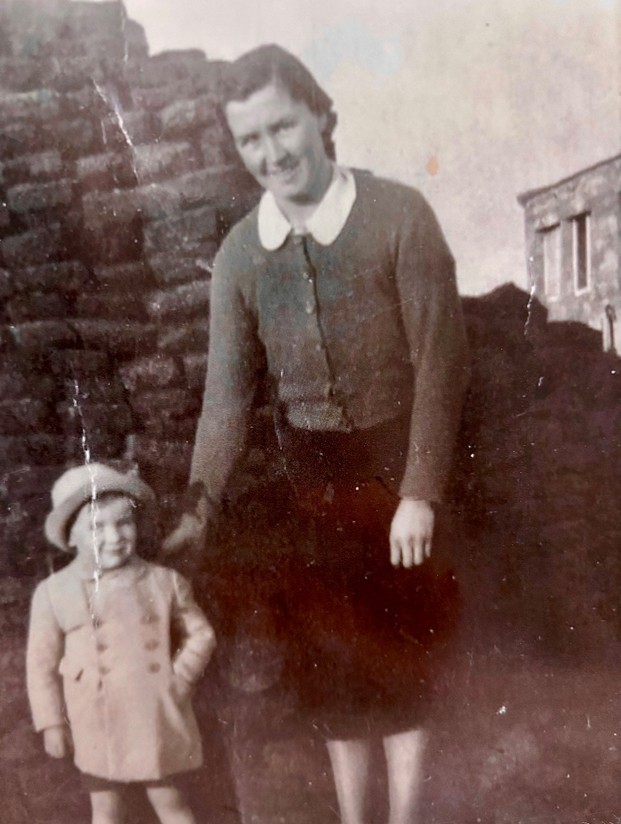

June 5, 1940, saw Grandpa billeted around St-Blimont, about 6 miles from St Valerie-sur-Somme, this being one of the areas held by the 7th and 8th Battalions of the Argylls. The German infantry was advancing rapidly, resulting in the death of many soldiers and the capture of many others, and by the end of that day, hundreds of soldiers were missing, including Grandpa. The War Office Casualty Section listed him as a missing casualty, a status that remained for nearly seven weeks, leading his family to fear he had been killed in action. However, news eventually filtered through that he was in German hands, having been captured at St-Blimont on Thursday, June 6. Upon hearing of his capture, Granny returned, with Neil, to live with her family in Kilmuir. From here she reminisced of looking out to sea and watching the Arctic Convoys heading to Loch Ewe in 1941, before their onward hazardous journeys to Russia.

Following his capture, Grandpa, along with hundreds of others, were marched through France, Belgium, and Holland. Early on this march, he walked alongside Private William Kemp, Corporal Sandy MacDonald, and Lance Corporal James ‘Ginger’ Wilson, with whom he had become good friends. Those three were planning their (now famous) escape, which involved speaking only Gaelic to conceal their identities whilst on the run. They were keen for Grandpa to escape with them, but he didn’t speak Gaelic and feared that this would expose them. While resting on a wall in France, the three men discreetly rolled off, and so began their dangerous but successful plan. The march continued until they reached the River Rhine, and from there, Grandpa was birthed on a boat and motored to Germany. Finally, he was transported down the Oder River and marched to a POW camp in Poland.

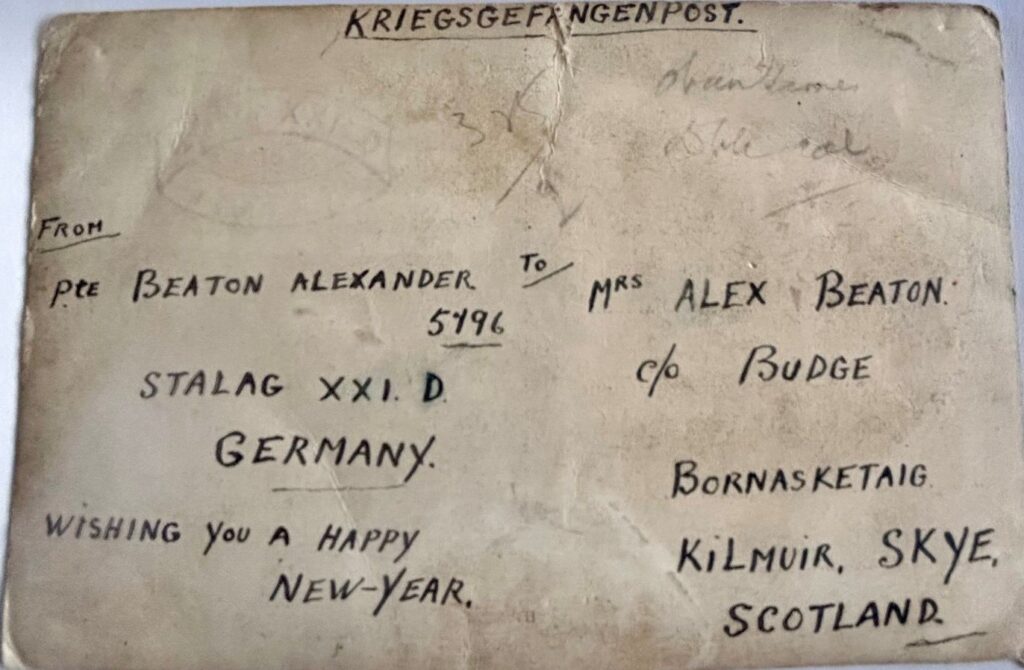

The first camp he was taken to was Stalag XX1B (formerly Stalag XXI-B2) located in Warthelager, just outside Posen, where he arrived around the end of July 1940. This is where he was processed and given his prisoner number. The Stalag camps were the main HQ camps, from which prisoners were then attached to working camps. Over the next 5 years, he was moved to various camps in Poland, including the following three:

- Stalag XX1D: 12th of September 1941

- Fort Rauch, Posen: 9th of December 1941.

- Stalag VIII B (renamed 344) Lamsdorf: 7th of April 1944

Work camps, or Arbeitskommando, usually abbreviated just to kommando, were small camps attached to main Stalags where prisoners were put to work. Typically, only privates and non-commissioned officers below the rank of Sergeant were sent to these camps, of which there were many thousands. Camps beginning with an “E” denotes “English” for British prisoners of war. Part of Grandpa’s work camp duty involved farm labour in Poland, and it was here that he learned to use an American style scythe to cut hay and make giant haystacks, skills he would come to utilise on his return home. On the 8th of April 1944, he was attached to the following work camp: E746 Stalag VIIIB Königshütte Poland Stone Quarry / Other work 601 (601 is the number of men working at the camp at that time.)

Like many of his fellow soldiers, Grandpa didn’t speak much of his time as a POW. However, he did speak of the extreme cold and hunger he endured but added that some of the German guards showed compassion. One memorable story involved the secret production of potato vodka with fellow POWs. They created a potato prodder by attaching a nail to the end of a broom handle. Taking turns, they poked the broom handle through a hole in the wall adjacent to the potato store, using the nail as a skewer. Additional ingredients, like sugar, were obtained from Red Cross parcels. One late evening, while tending to the vodka, Grandpa saw an ominous shadow on the wall in front of him. Turning around, he found a German guard and feared the worst. When the guard asked if he was making vodka, Grandpa nodded in the affirmative. However, instead of punishing him, the guard offered a deal and proposed that if he received a regular share of the vodka and the occasional bar of chocolate from a Red Cross parcel, he wouldn’t report the activity. This arrangement worked well for all those involved.

This compassion was further demonstrated when liberation of the camps began in 1945. He spoke of panic among some of the guards, and one in particular, with whom he had formed a good relationship, gave him his Luger pistol, saying that for him the war was over and that this might help protect Grandpa on the remainder of his journey.

On May 2, 1945, Grandpa was reported to the War Office Casualty Branch as “no longer a prisoner of war.” The location of his liberation remains unknown, but by the time he reached UK shores in 1945, he was in poor health and was admitted to the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital in Oswestry, Shropshire, where he underwent stomach surgery and rehabilitation. His physical recovery took several months and, consequently, he wasn’t discharged from the army until December 17, 1945, when he reunited with Granny and his six-year-old son in Kilmuir, Skye. Beyond the struggles of readjusting to civilian life, the reunion was further complicated by Neil speaking only Gaelic and Grandpa speaking only English.

After the war, Granny and Grandpa settled in Uig for a time, before eventually relocating to Erbusaig, near Kyle of Lochalsh, with a family which, by then, had grown from 1 to 7 children. He took a job as a guard on the Kyle to Inverness line and supplemented his income by tending a small croft close to his home. His fellow crofters admired his ability to hand-cut a large field of hay quickly using an American-style scythe. His European-style haystacks were also the talk of the surrounding villagers due to their unique structure and size: skills he learned as a prisoner of war.

Grandpa passed away in May 1982. As a mark of respect, on the day of his funeral, the train halted on the line above the family cottage in Erbusaig; a testament to how well-regarded he was by all who knew and worked alongside him.